This year, DANCE your way to Valentine’s Day! Novels based on fairytales and folktales featuring dance.

In preceding years (you can find all the posts archived on my blog, btw–just look for February!), I have posted novels based on worldwide fairytales and folk tales, and on two “literary” fairytales (Cinderella and Rapunzel). This year, I’m featuring a whole week of novels based on fairytales and folktales involving dance. Here are the posts:

Day One of Fairytale Fantasy Week: Entwined, by Heather Dixon–a novel based on the classic fairytale “The Twelve Dancing Princesses.” Find the review here.

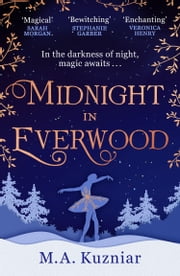

TODAY, Day Two: Midnight in Everwood, by M. A. Kuzniar–a novel based on the story behind the classic fairytale ballet, The Nutcracker.

Day Three: Valentine’s Day itself! The amazing fantasy novel Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell, by Susanna Clarke–a novel with a strong dancing subplot.

Day Four: House of Salt and Sorrows, by Erin A. Craig–another novel based on “The Twelve Dancing Princesses.”

Day Five: Dark Breaks the Dawn, by Sara B. Larson–a novel based on the fairytale ballet Swan Lake.

Day Six: Sexing the Cherry, by Jeanette Winterson–a final choice based on “The Twelve Dancing Princesses,” but be warned–it’s nothing like the others.

Day Seven: A wrap-up and a special exploration of the “dance mania” of the medieval period, plus a free download.

TODAY, a review of Midnight in Everwood, by M. A. Kuzniar

Midnight in Everwood (2022), by M. A. Kunziar, published by HQ (an imprint of Harper Collins), bills itself as an “historical romance.” It’s set in Edwardian England, and the author has clearly and well researched the era. References abound to all things of the era, and to the locale of the (realistic) part of the story, Nottingham, England. They are sprinkled everywhere. As an admirer of historical fiction, I appreciated the authenticity, although I have to admit these references were sometimes not smoothly integrated into the narrative but kind of stuck in there to signal that we’re reading about a real place and time. That’s important, though, because the novel gives us the realistic setting as a wrapper around (forgive me for giving in to the impulse!) a candy center set in a candy fantasyland. The story centers on Marietta, a young woman committed to her passion and talent for dancing ballet. Unfortunately for her, she is the daughter of a very proper and upwardly-striving Edwardian family. They’ll never let her dance professionally, and they insist that she marry, or they’ll cut her off from her inheritance. If you love Regency romance, you know this means social death to a young lady. Marietta’s last chance to dance will be at her parents’ annual Christmas Eve ball, where a family friend has erected an elaborate stage set. The friend, the mysterious and wealthy Dr. Drosselmeier, is also Marietta’s suitor. When Marietta flees backstage from Drosselmeier’s unwelcome advances, she hides in–get this–a wardrobe, which leads into a magical snow-kingdom. This is where the novel moves from romance–historical romance, at that–into fantasy.

The Nutcracker–the tale

Recapping what I mean by “fairytale”: No fairies are necessarily involved. The term has evolved to refer to a particular magical type of folk tale that may involve fairies, princesses, and the like, but may not. (A subgenre of fantasy, involving the fae, is an entirely different matter). And sometimes, what readers have come to know as “fairytales” aren’t any such thing–not folklore, passed down anonymously through the generations and centuries, often by word of mouth, but literary creations by artists hoping to mimic the fairytale aura. I should also mention that my blog posts on this subject won’t refer to anything Disney, except in passing. The Disney take on fairytales occurs in a whole world of its own, it has its faithful fans, and I don’t intrude there.

The Nutcracker ballet, with music by Tchaikovsky (and, traditionally, choreography by Marius Petipa), was first performed in 1892 and has become one of the most famed and beloved in the Western canon. You can watch a version here. The ballet is based on a tale, “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King” (1819), by the German author E. T. A. Hoffmann, a writer who specialized in what we often now term “literary fairytales.” There might be some folk underpinnings, but Hoffman made these stories up, so they are not true folk tales (a.k.a. fairytales). But generations of readers and viewers have regarded them as fairytales anyhow, the same way they regard Cinderella and Rapunzel, two other literary creations. The ballet is actually based on a retelling of Hoffmann’s story by Alexandre Dumas, the famous author of such fat, beloved novels as The Count of Monte Cristo and The Three Musketeers. So the Nutcracker story has great artistic chops, and it has been adapted in many different ways and in many different forms over the years.

In Hoffmann’s tale (and Dumas’s retelling), a mysterious toymaker named Drosselmeyer brings toys to the family of a young girl, Clara (in some versions called Marie). The girl is drawn to an ingenious nutcracker dressed like a toy soldier (by now a fixture in Christmas pop culture). The girl has a dream in which toy soldiers led by the valiant nutcracker battle an army of mice. She is whisked to a magical forest, where the nutcracker turns into a human prince and gives her a marvelous tour of the Land of Sweets. Details of the story vary from version to version, but those are the basics.

My thoughts on this book:

This novel tries so hard. The historical details are authentic, although they tend to be shoved in the reader’s face. The ballet details. . .let’s just say I don’t know much about ballet, but I believed every word. I think this is the place the novel shines. Others more knowledgeable than I am may have a more informed opinion. Send in a comment if you’ve read the book and agree/disagree/want to add more. But anyway, I loved the combination of ballet as an art and practice with the re-envisioning of a beloved ballet’s story.

When Marietta gets to the land of sweets, though, the book goes a little sour on me. I mean, every single piece of candy, slice of pie, whip of meringue that can possibly be described. . .is described. My cavities began to ache. Again, though–especially in romance literature, there’s an entire subgenre of baking romance. No, seriously. So there are readers who may love this whole aspect of the novel even if I didn’t.

The main reason the novel fails to win me over is its writing style, however–so overly formal it tilts into awkward, and then at times floridly over the top. This novel does have its fans, though. You, dear reader, know yourself. You might just love it.

A fascinating side note:

Did you notice that Marietta goes through a wardrobe to get from the real world to the fantasy world? Wow. Shades of C. S. Lewis. “Portal fantasy” in which characters make that transition use similar devices all the time–think of Harry Potter and the train station–but a wardrobe? I only know of one other, the one in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe and its siblings. I tried looking up this plot point to see if anyone had ever noticed and discussed the similarity, but I didn’t get very far. Again, readers, if you know more than I do, let me know in the comments.

Content warnings:

- Ok, don’t give this novel to a very young teen to read, at least not without thinking about your teen’s level of maturity. Partly, the book is fantasy. Partly, it’s romance. If you know anything about romance novels, you know they come in flavors: “sweet,” “clean,” and “low-spice,” but also “hot,” “spicy,” all the way to erotica. In a “low-spice” romance novel, there may be a sex scene or two, but these scenes are either “closed door” (as in, you know what’s going on behind the door but the writer doesn’t spell it out) or “fade to black,” as in a sedate movie that looks away from the naughty bits. There’s a scene in this novel that is not really spicy and explicit, but not exactly closed-door or fade-to-black. Just saying, for those who worry about these things. I actually don’t (as evidenced by my own novels, which are not. . .quite. . .YA. . .enough sometimes), but some may.

- Toothache.

My experience buying this book:

I read this book through the Kobo app on my iPad. Getting the book, for me, wasn’t as straightforward as buying a book for my Kindle device, but it was pretty easy, or would have been if not for a glitch in the app. I’m sure if I had a Kobo reading device, buying the book there would have been just as easy as buying on my Kindle. As it was, I needed to go to the Kobo web site and buy it from there (note–I’m using the U.S. site. Your experience may be different if you are reading from a country other than the U.S.). By the way, you can enroll in the Kobo Plus subscription service to read many ebooks free.

Once I had purchased from the Kobo web site, the book appeared on my iPad’s Kobo app–or would have, if not for one glitch, when nearly all of my books on Kobo disappeared from the app. I had to delete the app and re-install it to see my books. That was a pita. The problem, though, is not Kobo’s. It’s a problem Apple created when it ensured that only its own iBooks store could process ebook sales directly from the app. That’s good for Apple’s bottom line, not so great for readers who get their books elsewhere.

One solution: buy a paperback or hardback copy from your local independent bookstore! (oh, all right, from a chain big box bookstore, I guess, if you just have to.) I myself am hooked on the convenience of ebooks, but you don’t have to be. AND THE LIBRARY. In the U.S., your public library is full of free-to-read ebooks. I’m not sure about library policies elsewhere.

Pingback: Valentine Week, Day Five: Fairytale Fantasy – Fantastes

Pingback: Valentine Week, Day Six: Fairytale Fantasy – Fantastes

Pingback: Valentine Week, Day Seven: Fairytale Fantasy DELAYED! – Fantastes