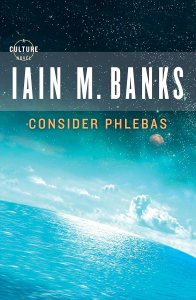

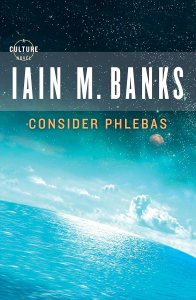

Iain Banks, Consider Phlebas, 1987–the first book in the magnificent Culture series. Banks is a superb writer, not only of SF but of conventionally realistic novels as well.

Iain Banks, Consider Phlebas, 1987–the first book in the magnificent Culture series. Banks is a superb writer, not only of SF but of conventionally realistic novels as well.

Kim Stanley Robinson published The Ministry for the Future in 2020, a cautionary tale for our planet on the brink. The book is chilling and in my opinion necessary. The novel is one among many, and one of the best, in Robinson’s prolific career.

I should also point you to a great review of Icehenge, one of Robinson’s other novels, recently posted HERE.

Cecilia Holland, widely admired for her historical fiction, published her only SF novel, Floating Worlds, in 1976. It ought to be better known! It is one of my favorites. It’s a space pirates novel. It’s the Mongol Horde in space. It’s a novel of political intrigue. It’s a novel with some of the most compelling characters ever written, especially the tough female main character. (There is one unfortunate turn of phrase in it that may give the contemporary reader pause, but read past that and give the novel the benefit of the doubt.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.