The Hugo Awards for 2025 are soon to be announced. Here is the list of finalists for best novel:

- The Tainted Cup by Robert Jackson Bennett (Del Rey, Hodderscape UK)

- The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley (Avid Reader Press, Sceptre)

- A Sorceress Comes to Call by T. Kingfisher (Tor)

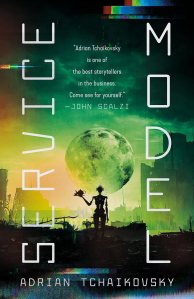

- Service Model by Adrian Tchaikovsky (Tordotcom)

- Alien Clay by Adrian Tchaikovsky (Orbit US, Tor UK)

- Someone You Can Build a Nest In by John Wiswell (DAW)

The winner will be announced on August 16, 2025 at Seattle WorldCon. That means you, Reader, have time for some catch-up reading if you haven’t gotten around to all these wonderful novels. I had a fairly easy job of it, since several of the novels on the Hugo list were also short-listed for the Nebula and Arthur C. Clarke awards, and I had already read them before the Hugo finalists were announced.

Disclaimer: I only review the novels. Yet so many wonderful reading experiences await in the other categories! Go to the Hugo Awards web site to find them all.

In the next several posts, I’ll review the short-listed Hugo Awards nominees for best novel.

As always, I need to mention the latest controversy roiling the Hugos. It seems one of these rears its ugly head every year or so. Last year’s controversy was about alleged censorship related to the WorldCon host for the 2024 awards, China. This year’s is about AI. How trendy. Several officials of WorldCon have resigned over the brouhaha. Briefly: In order to cut down on workload BUT ALSO to deal with possible sensitivity issues in the U.S., the WorldCon officials vetted their panel of judges using ChatGPG. Unfortunately, these AI tools are notoriously unreliable, and often seem to reflect possible prejudices. The use of the tool may have helped out with the workload, but how trustworthy was the resulting panel? The decision to use AI for this purpose was also hugely tone deaf, considering the widespread distrust and animus that the SF community feels toward such tools. Find an account of the controversy HERE.

AI in general, and especially for writers, is a magnet for controversy. The Hugos controversy, thankfully, didn’t involve any use of AI by writers, but it does (or did, until WorldCon took corrective action) impugn the integrity of the award, one of the longest-standing, most respected awards for speculative fiction. As a writer myself, I found this blog post–on the Hugo controversy specifically and the use of AI by writers generally–to be especially interesting. How far should the literary world and individual writers go in embracing these tools flooding into the creative process?

For myself, I don’t use it–I say. Then I think again. But I never use grammar checkers, because in my experience they are dead wrong too much of the time and give bad advice even when they are (sort of) right. Good grammar–good. Good grammar used slavishly–wooden writing. (You see those two sentence fragments I just used?) I do use spell checkers, although not all the time. When I do, I use them very judiciously. They too can provide misleading or just wrong advice. I’d rather risk the occasional typo, which comes to us all. And those are very, very basic uses of Al. Generative AI to write a novel? Horrible, horrible idea. Generative AI to plot a novel, organize time, create marketing copy, and so on? Iffy at best.

AND THEN I climb down off my high horse to realize I have sometimes used AI-generated illustrations for this very blog. I am resolving right now not to resort to that in the future. More problematic for me: As a starving artist, I can’t afford to hire a voice actor to narrate my novels. Do I use AI-generated voices, especially considering how many consumers of fiction get their jollies from audiobooks and not the kind you process with your eyeballs? I’m thinking about it. Am I wrong? Am I a hypocrite? The horror! The horror!

NEXT UP: Reviews of short-listed novels by Robert Jackson Bennet and Kalianne Bradley.

You must be logged in to post a comment.