Fairytale Fantasy Week starts TODAY here at fantastes.com. We love Robin Hood. Don’t we? So why is it so hard to find decent fantasy written or filmed about/around the popular rogue? I know I say I’ll never write about Disney, but oodalolly, people, the 1973 Disney cartoon might be the best of the fairly recent takes on this enduring story.

First, a look backward. Where did Robin Hood come from, anyway? That’s question #1. Then: why were 19th century English authors so fond of the green-hooded fellow, and what did they write? Finally, maybe unanswerable: What is it about HOODS that so intrigues people? Last year’s theme was Little Red Riding Hood. This year’s is the green-hooded Robin. Here’s a general recommendation. If you want to know all there is to know about Robin Hood without getting all scholarly about it, you’d do well to head to the Robin Hood Wikipedia page. Best of all, the Wikipedia entry gives you an extensive bibliography in case you want to take a deeper dive.

Where did Robin Hood come from?

Countless scholars and others have speculated that Robin was based on a real person. The consensus? Maybe. Probably not. This site gives a good quick overview of all the speculations and connections of Robin to actual history.

Whether he really lived or was based on someone like him, some bold and gallant rogue who robbed from the rich and gave to the poor, he was and remains an iconic figure in the folklore of the British Isles. He figures especially as a beloved hero in many of the Childe ballads–folksongs based down through the generations and collected by 19th century anthropologist Francis Childe.

Why was 19th century England so enthralled with Robin Hood?

Anthropologists and folklorists like Childe. . . writers of popular and “literary” and children’s fiction. . . What was it about Robin Hood that fascinated them so completely? One answer: England’s emergence as a world power. Often, a society in this position examines its origins and its heroes and elevates them to consolidate its place in the world. For example: in the age of Augustus Caesar, the poet Virgil wrote his great epic The Aeneid as a way to say to the world, hey! Rome has its Homeric epic too! Rome has heroic origins–we’re not just some backwater Italian bunch of thugs who made good and bullied our way to world domination. For example: in England itself, the stories of King Arthur emphasized the honor and glory of English origins. For example: in France, the tales of Charlemagne did the same.

The heroic deeds of King Arthur and his knights had captured the English imagination in the medieval era and just kept gaining traction, so that in the Victorian era, the triumphant phase of the British empire (“the sun never sets on the British empire”), Arthur became a powerful symbol of national pride and might.

Robin, though, was a humbler sort of hero. Maybe a hero for the people. In Primitive Rebels: Studies in Archaic Forms of Social Movement in the 19th and 20th Centuries (Praeger 1959), British historian Eric Hobsbawm identifies Robin Hood as the typical example of the “social bandit,” seen by the poor as a figure of protest against oppression. They “protect the bandit, regard him as their champion, idealize him, and turn him into a myth” (p. 13). Here’s a good quick site that summarizes that particular Robin Hood theory.

The Robin Hood Childe ballads:

Childe made it his mission to go around the British Isles collecting folk ballads, storytelling in musical form, invented to entertain mostly illiterate people in an era where most people did not read or have easy access to written material. Robin Hood was such a prominent subject of these ballads that Childe devoted a large part of his study to them.

No one knows who invented these ballads first or, often, what their deep origins might have been, but the earliest references to Robin Hood show up around the 14th century, with indications that the legends surrounding Robin Hood may date from even earlier. The ballads Childe collected date from later on–15th and 16th centuries. This web site lists every Robin Hood ballad in the Childe texts–very useful!

Here’s an excerpt from one of the most popular, although this one was printed in S. C. Hall’s The Book of British Ballads (1842):

Because of this 19th century upsurge of interest in folklore, in the British Isles and elsewhere (the Grimm brothers in Germany engaged in similar efforts, and there were others), literary writers began to mine popular folklore for the subjects of their books.

One of the most famous: Sir Walter Scott, a prolific writer of historical (and other) fiction, one of the most celebrated novelists of his day. He used the Scottish Jacobite Rebellion, the court of Queen Elizabeth, and the adventures of Rob Roy MacGregor (a kind of Robin Hood figure) as backdrops for some of his novels. While he never wrote a pure Robin-Hood-themed novel, the most famous of his historical novels, Ivanhoe, features the hooded rogue prominently and embellishes the idea that Robin was involved in the conflict between the Saxon natives of England with their Norman French overlords during the reign of Richard I. In Ivanhoe, Scott combines Robin’s well-known traditional story with his own fictional tale of a Saxon knight’s battle to regain his inheritance. Then Scott further brings in the (sort of) historical account of Richard I’s struggle to wrest his kingdom from the hands of his treasonous brother John. In combining his own imagined tale of a rebel knight with both folklore (Robin) and history (Richard the Lion-hearted), Scott cooked up a literary best-seller.

The novel (and all of Scott’s work) has fallen out of favor recently, not least because Ivanhoe (reflecting the culture from which it emerged) is hideously anti-Semitic, but Scott is universally lauded for his contribution to the development of the historical novel. That subgenre, I contend, should be considered speculative fiction just as much as science fiction. We can’t really retrieve the past–we just think we can. But it is as remote from us as Mars, and just as much subject to imaginative speculation based on (scientific? historical? fact). And the historical novel is also a ripe genre for hybridization with fantasy elements. Think, for example, of Madeline Miller’s Circe, or Susanna Clarke’s absolutely magnificent Jonathan Strange & Mister Norrell.

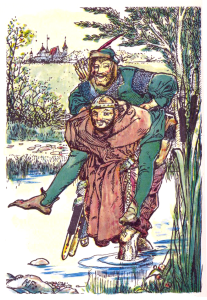

One more 19th century example: Howard Pyle. Pyle was both a writer and an illustrator specializing in editions of adventure stories for children–actually, by his lights, boys, but pfft, we girls have enjoyed them too. Pyle often chose beloved traditional adventure tales to illustrate and retell. He illustrated a popular collection of pirate stories, a volume of King Arthur stories, and also a compendium of Robin Hood stories, which he stitched together into a novel: The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood (1883). You can read these free on Project Gutenberg, but I found it difficult there to access Pyle’s marvelous illustrations. I had more luck at the Internet Archives web site. Here’s one of Pyle’s Robin Hood illustrations. This one depicts the story of how Robin Hood induced Friar Tuck to take him across a river on his back. Thigh-slapping hijinks ensue. And by the way, Robin Hood’s men are called “merry” in the medieval sense of “stout-hearted,” “stand-up.” But of course we modern readers think “merry” and we think “guffaw.” Therefore, in modern Robin Hood retellings, the merry men are always yucking it up. Sometimes they are in the ballads too, to be fair, and the medieval origins of “merry” do mention jollity along with mere agreeable or pleasant or stalwart traits.

The takeaway: Robin Hood is a figure who has been popular among English-speaking peoples since at least the late medieval period, and probably earlier. He enjoyed a big revival of interest with the 19th century rise of folklore studies. That interest continued into the 20th century, especially when the new medium of film (like all new media), hungry for content, voraciously devoured Robin Hood and spit him out onto celluloid. More about that in a later post. It remains to see whether the Brave New World of the 21st century will find Robin as fascinating as earlier centuries always have–at least in the English-speaking world–but isn’t the underdog rogue or outlaw figure always fascinating?

So onward into fairytale fantasy week, in which I will explore my own Robin Hood categories–not scientific, especially because they overlap quite a bit:

- Some interesting Robin Hood retellings

- Robin Hood favorite characters

- Robin Hood revisionist history

- Robin Hood on film and other media

- Other rogues we love, perhaps influenced by Robin, the arch-rogue himself

- My favorites

Oh, yes, that hood thing. What is it about the hood? A lot of these stories, including Robin Hood and Little Red Riding Hood, originated in the medieval period, where hoods were a prominent part of the peasant wardrobe. Here’s a nice overview.

But why do we still like the hood? Sometimes we like rogues who don’t wear hoods. I mean, Zorro, a Robin Hood-type figure, doesn’t have one. He does have that mask, though. . . Maybe it’s enough to say we love an underdog, we love a sassy rogue who flouts authority, especially an oppressive authority, and leave it at that.