Here’s the last in my series of posts reviewing six SF novels with alien communication as a main plot point:

- China Miéville, Embassytown

- Ann Leckie, Translation State

- Ray Nayler, The Mountain in the Sea

- Adrian Tchaikovsky, The Children of Time (book 1)

- Cinxin Liu, The Three-Body Problem

- Ursula LeGuin, The Dispossessed–reviewed in this post

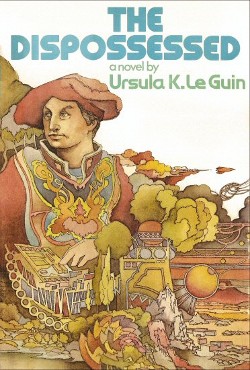

The Dispossessed, Ursula LeGuin, 1974

LeGuin’s amazing book in her Hainish cycle won the Nebula (1974), Hugo, Locus, and Jupiter (1975) Awards for best novel. It’s the story of a scientist from a utopian anarchist society who attempts to share new important knowledge with a neighboring militaristic society, and at great personal risk. One interesting side-issue in The Dispossessed is the brief explanation of one of LeGuin’s more enigmatic SF inventions: the faster-than-light communication device called the ansible.

It’s easy to take the ansible mention out of context, because The Dispossessed is not essentially about alien communication at all. But I am intrigued by how this device popping up repeatedly in LeGuin’s fiction–and seemingly reverse-engineered in The Dispossesed to create an origin story for it–really might be about a different communication problem entirely. This is why many readers think LeGuin’s work transcends genre, why you might need to take it out of the SF framework. I don’t mean take it out entirely. The SF genre and tropes give LeGuin the means to write about what really moves her–and us, the readers.

Throughout LeGuin’s Hainish cycle of novels, the ansible has allowed people to communicate instantaneously across stars and galaxies. The online Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction details where you can find these references in LeGuin’s fiction. Similar to the way Isaac Asimov’s invented word robot was taken up by other writers, a number of writers of SF have appropriated LeGuin’s ansible, as the dictionary entry shows. Unlike robot, ansible did not go on to become a household word. While robots are feasible, more and more so as the years roll on, faster-than-light communication is not.

Or is it? On the face of it, the ansible is a space opera-type solution similar to the one in Cinxin Liu’s The Three-Body Problem (see the preceding post). Neither is a physically possible or plausible technology, although perhaps Liu’s quantum entanglement explanation for his sophons might make it seem more so. (HERE is an argument counter to mine.)

In LeGuin’s fiction, the reader simply accepts the ansible as part of the world-building. Why do I accept such a device–or, well, “willingly suspend my disbelief” about it–in LeGuin’s novels but not in Liu’s? LeGuin’s brilliant writing and her insights into the way culture shapes communication overwhelm any skepticism I might have about an “ansible.” I don’t get sucked into the author’s vision in The Three-Body Problem as powerfully. AND YET: what we will swallow in the name of fiction varies depending on who is doing the reading, maybe more than who is doing the writing. So it may simply come down to a matter of taste that I sail right past the ansible but not the Trisolarans and their sophons.

In The Dispossessed, LeGuin suggests an origin for the ansible in the theories of her main character, a scientist. The word ansible itself doesn’t have any scientific basis. LeGuin supposedly said she had been trying to make up a term suggesting “answerable.” As The Dispossessed begins, her scientist character Shrevek is about to leave his isolated utopian anarchist home on the moon Anarres. He will travel to the moon’s planet, Urras, where he hopes to share his new theoretical understanding with a wider audience. Shrevek is motivated by the benevolent wish to do good to all humanity. As a young man, he wrote a paper on a topic known as Relative Frequency, which got him the attention of senior scientists on the moon world–but also got his work quietly suppressed. Now what LeGuin calls his General Temporal Theory is highly sought after on Urras. Beyond a fun shout-out to Einstein, LeGuin doesn’t go into detail about these theories.

Scientists on Urras flatteringly encourage Shrevek to defect to their planet, where he can be properly appreciated. Shrevek doesn’t fall for the flattery, but he does see an opportunity to disseminate his theory. Once he gets to Urras, however, he gradually realizes how deeply he is being used; that the warring powers on Urras hope to misappropriate his discovery to dominate their world and beyond. He doesn’t even write his theory down, keeping it all in his head. Otherwise, as one of the faction leaders warns him about a rival faction, “They’d have it.” And, presumably, use it for warlike ends. Trapped in this nest of rival conspirators, Shrevek has to decide how to keep his integrity intact, and his theory safe.

Among the applications of Shrevek’s theory is the faster-than-light ansible, which has made its appearance without much explanation in a number of LeGuin’s earlier Hainish novels.

I really love this book. I don’t think it answers any questions about alien communication, not really. The ansible remains a space opera device; Shrevek’s General Temporal Theory is never really described. It remains a MacGuffin, a fictional device without any inherent meaning of its own except to drive the plot. What are we to make of it, then? Why is it in the novel, and did LeGuin really mean for it to form the underpinning for her ansible communication device?

I think Shrevek’s theory should be understood more as a symbol than either an exploration of a real theory, on the one hand, or a convenient space opera trope, on the other. Here in LeGuin’s self-described “ambiguous utopia,” Shrevek’s discovery holds infinite promise for good yet is inevitably in danger of becoming corrupted, held hostage to the worst elements of human nature. Perhaps we can see Shrevek’s theory as a stand-in for the potential that inheres in our nature and keeps struggling to emerge, even while other forces attempt to buy it or destroy it.

Perhaps we readers are asked to see Shrevek’s divided planetary system as a stage to play out humanity’s age-old dilemma. The ending of the novel asks that question, I think, and the jury is out: how we will answer it and whether in our answer we will end up thriving or destroying ourselves. The communication issue is our own, the conversation we are continually holding inside ourselves and in the larger society, not some alien out-there consciousness. What is right? What is the good? And do we strive to serve the good, or our own base grasping after power and possessions? The Dispossessed is a novel of and for our times.

With that to mull over, here’s the next. . .

Speculative Fiction Advent Calendar of quotes. Quotation for Day Five, Dec. 5, 2025: