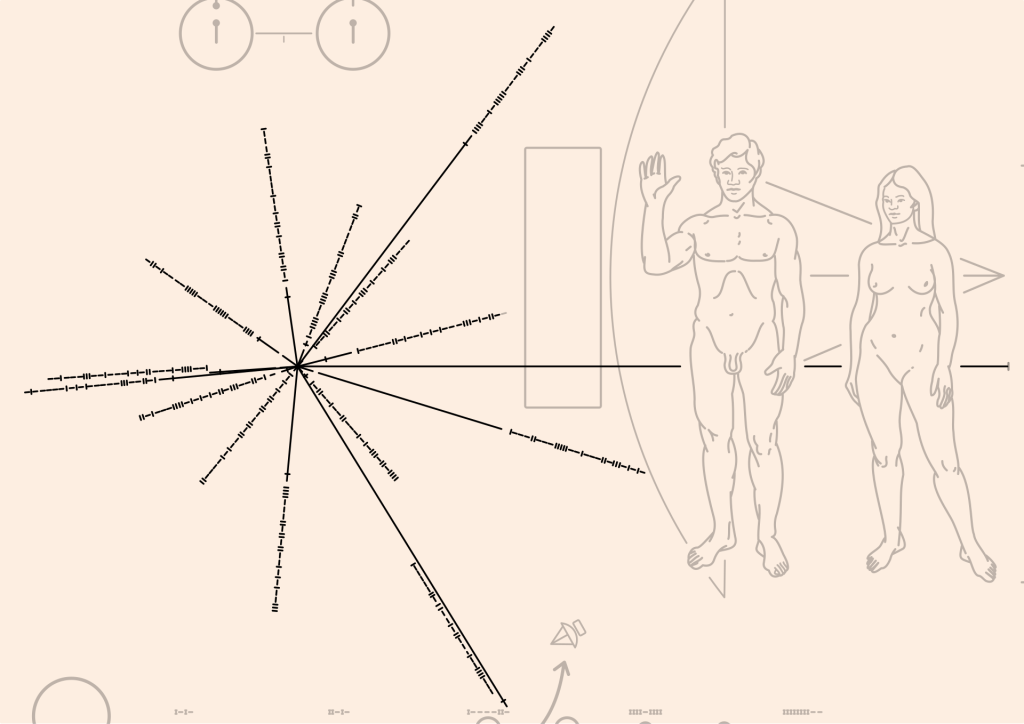

Communicating human to alien–a lot of SF makes it sound like a snap, when of course it couldn’t possibly be. Here’s an article that explains a little about xenolinguistics. Here’s another. Those communications from NASA on the Pioneer plaque and the Voyager golden record are unlikely to communicate anything explicable to any random alien who might intercept them.

What WILL they make of those anatomically-correct drawings sent out with the Pioneer 10 and 11 spacecraft? Suppose the aliens on the receiving end are not mammals? Maybe the Pioneer plaque, to use just that one example, tells US a lot more about us, and us at a single point of time, from the perspective of one human society, than it might tell any mysterious Them out there. Take a look at that dominant clearly Caucasian male, the one doing the hailing, and then that shrinking helpmeet woman hanging diffidently at his side.

If we ever do encounter an intelligent alien species, we’re very likely to have no idea how to communicate with them, probably no earthly way to do it.

Yet we humans want to think we can. And SF, our fictional form of dreaming about such matters, keeps trying. What SF novels and other forms of storytelling get it right? Which ones get it laughably wrong? Which ones don’t even care, because they’re trying for something else entirely? Here is a very partial list in no particular order:

- Frank Herbert, Dune (1965)–Telepathy! Bene Gesserit superpowers! It seems silly, except a novel like this has so many other things going on in it that you don’t stop to think how silly. That said–this novel is set in a galaxy far, far away, a culture very far removed in space and time from Earth’s. So anything may be possible!

- Ursula LeGuin, The Left Hand of Darkness (1969)–Empathic powers, the “mindspeak” used by Terran diplomatic envoy Genly Ai, allow him to communicate with the inhabitants of an alien planet. LeGuin’s version of telepathy is complicated and deepened by the sociocultural expectations of sender and receiver. I believed in it as a reader because, even though LeGuin never explains its physical processes, the psychological and sociological implications of its use are a main plot element and a main way she builds her characters, all masterfully handled. Further, the indigenous inhabitants of the planet (the “aliens”) engage in a complex cultural practice known as “shifgrethor.” Ai, who is of Terran origins (someone like us) must learn to understand this alien system of honor and face-saving before he can resolve the diplomatic problem he has come to the planet to address. LeGuin shows us how such cultural practices are just as much aspects of communication as language. And as for communication over long distances. . .I will save her concept of the “ansible” for another post.

- The Star Trek universe (original StarTrek series, created by Gene Roddenberry, first aired in 1966–many spinoffs on film and television since): The actor James Doohan, who portrayed the character Scotty in the original Star Trek series, purportedly invented a few words for the hostile inhabitants of the Klingon empire to speak. Later, as the idea of the Klingons grew more important to the invented world of the series, American linguist Marc Okrand developed a real, if limited, Klingon vocabulary and ruleset. Since then, actual people have used the Klingon language in actual situations, and its uses have expanded in unexpected ways (“You have not experienced Shakespeare until you have read him in the original Klingon”–the Bible translated into Klingon– etc.). If you’d like to go down this particular rabbit hole, the Klingon Language Institute is a good place to start. So–the Star Trek characters encounter aliens who speak Klingon, but it’s as if a German speaker encountered a speaker of French. It’s simply another language spoken by another human-ish group, and while you might need to consult your Klingon dictionary, you never get that WTF? experience that you might have if you are accosted by an alien without, say, a mouth. (On the other hand. . .I’m thinking of “The Devil in the Dark,” episode 25 of the original series’s first season, aired in 1967, when Mr. Spock communicates telepathically with a being resembling a mobile rockpile. Through the famed Vulcan Mind Meld, Spock empathizes with its pain. . .then it turns out the rockpile can write in English. . .🤷♀️)

- The Star Wars universe (media franchise beginning with the first film directed by George Lucas in 1977; many books, movies both live and animated, streaming shows later, and the franchise is owned by Disney and keeps on keeping on): Another story-verse where citizens of a far-flung galactic empire speak all sorts of languages, but nothing a subtitle or two can’t demystify, even though some of the citizens look distinctly anatomically unhuman.

- Close Encounters of the Third Kind, dir. Steven Spielberg (1977): The aliens communicate with us partially through a telepathic dream-state summoning certain carefully-vetted humans to Devils Tower, Wyoming. The manner of first contact is a succession of musical tones, a universal that supposedly transcends culture and even species. But does it? What if your species doesn’t communicate through sound at all? I suppose these particular aliens have come to communicate with us particular humans, who do use sound, so okay. And it’s very cinematic. Who doesn’t hear those five notes in their heads? From the same director–ET, the Extraterrestrial (1982), about an alien stranded on earth. He telepathically connects via his iconic finger touch with the kids who discover him, although he needs their help to phone home. Maybe the whole enterprise of fictional alien communication becomes easier to swallow when it’s the aliens trying to communicate with us.

- Iain Banks, Consider Phlebas (1987): As in the other books of the author’s amazing and wonderful Culture series, the characters may speak different languages in their far-flung clashing galactic empires, and some might have difficulties with each other, but hey, nothing a galactic Duolingo course can’t fix. Horza, the main character, speaks the language of the Culture empire, although it’s not his native tongue, and that language serves as Lingua Franca for most of the humanoid characters. But his allies, the alien species called the Idirans, speak a language perfectly understandable to him too, in spite of a very, very different biology and physiognomy. It’s Space Opera-land, and of the highest, most enjoyable order, too. Every few years I have to re-read this novel!

- William Gibson, Neuromancer (1984): People rely on implanted translation devices. This is a very tidy, very popular way to solve the SF problem of the alien encounter–the translation device or technology or (wincing here) creature–see Douglas Adams’s hilarious The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (1979) and the babel fish that burrows into your ear. Of course, all you really need to know is. . .42.

- The Twilight Zone “To Serve Man” episode (aired in 1962, based on Damon Knight’s short story published in 1950): Sure, when the aliens arrive, you may not understand them, even big clumsy Lurch-type giant ones who can speak YOUR language and look, in retrospect, like SNL’s coneheads. But with a lot of study, you can figure out their mysterious writings. Don’t ingenious humans always? Spoiler alert: It’s a cookbook!

COMING UP NEXT: Novels that have seriously tackled the alien communication problem